It’s a story that still fascinates artists, storytellers, and generations of Welsh people. How did this part of Argentina become the far-flung corner of Wales? Why did 150 Welsh people travel 8,000 miles across the Atlantic to establish a remote community in South America? And how did they survive, given they arrived there in midwinter, 1865, not finding the verdant land they were promised?

The answer is a story of co-operation, companionship, resilience, and some extraordinary dreamers.

In early 19th century Wales, Welsh speakers, many of them non-conformist Christians, felt they were being persecuted for their language and culture. An 1847 parliamentary report on Welsh education (later known as The Treachery Of The Blue Books) made matters worse by making disparaging comments about the Welsh language. Pouring scorn on Welsh speakers, and advocating punishments like the Welsh Not (a piece of wood given to children who spoke Welsh in school, often hung around their necks), it prompted waves of migration from Wales to America. One non-conformist minister from Bala who had moved to Ohio, Michael D. Jones, knew how hard it was for the Welsh language to thrive in its motherland. The idea of creating a remote utopia away from the influence of the English language became his obsession.

A Caernarfon-born publisher and printer named Lewis Jones felt the same way. In 1862, he travelled to Patagonia's Chubut Valley, accompanied by Welsh Liberal politician Sir Love Parry-Jones (whose home estate, Madryn, would give its name to the port in which the settlers landed) . They were offered land by an Argentinian minister, despite the region already being occupied by an indigenous tribe.

Later that year, a pamphlet selling Patagonia's virtues was written and distributed back home, by another Welshman, Hugh Hughes. Hughes' promises of a land much like Wales were somewhat overstated. Despite this, the pamphlet convinced 150 people, many from the Cynon Valley communities of Aberdare, Mountain Ash and Abercwmboi, to board a tea-clipper boat, the Mimosa. Disembarking on 28 May from Liverpool, their mission was to set up a new Welsh settlement. They would call it Y Wladfa.

Establishing Y Wladfa

Two months and four days later, the Mimosa arrived in Patagonia. This was not the idyll they had been promised. It was midwinter, and the Chubut Valley was dry after a prolonged drought. Flash floods followed, destroying one of the early Welsh settlements. Fresh water was also difficult to find in these early years, before one party member, Rachel Jenkins, made a plan to irrigate the land. Later that century, wheat crops were popular and plentiful.

The Welsh were also helped by many of the Tuhuelche people. They taught the Welsh to hunt, and bartered guanaco meat for Welsh bread, helping them settle into their new home.

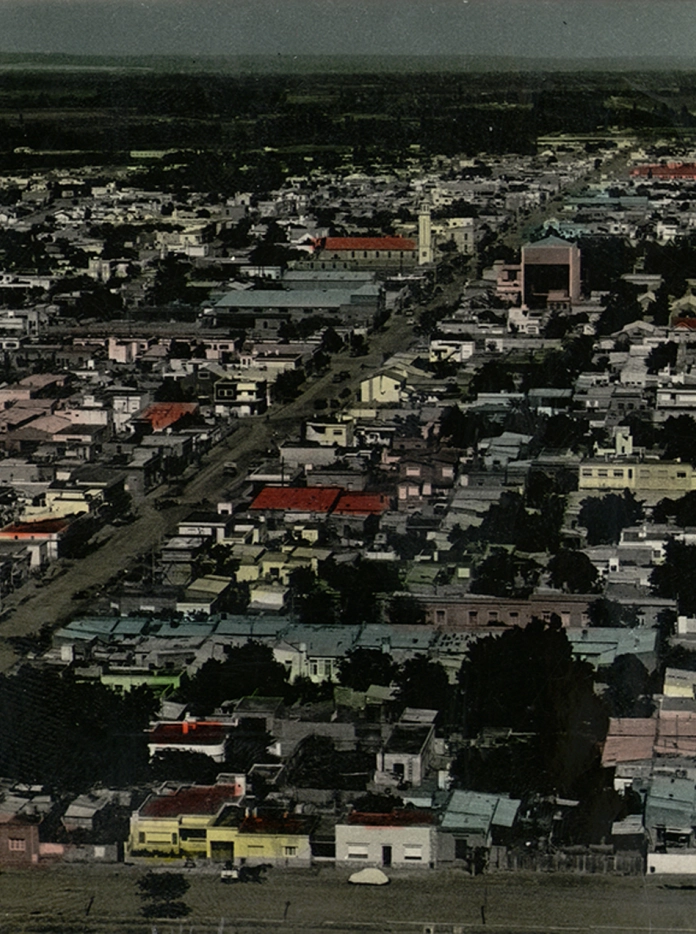

The first settlements were established on the east coast, and many survive to this day. Puerto Madryn is now a city of 100,000 people, home to a huge aluminium plant, and a thriving tourist spot for whale watching. A statue of a Welsh woman stands on the portside, staring inland, reminding visitors of how it all began. Fifty miles south is Trelew (“tre” for town, “Lew” for Lewis Jones), an active hub for the wool trade. It hosts the region’s annual Eisteddfod, and is home to several bilingual Welsh and Spanish schools. Around 30 Welsh Protestant chapels also dot the landscape, with recognisable names like Moriah and Tabernacl.

Nine miles upriver is Gaiman, home to the Museo Histórico Regional celebrating Welsh history. This is housed in the old railway station which served the late Victorian Chubut Railway (a project also driven by Lewis Jones) which helped the region to grow. Welsh tea houses are still popular here, selling a Patagonian relative of the Welsh bara brith cake, called torta negra in Spanish, or cacen ddu in Welsh; the village of Dolavon is also nearby (dol means meadow in Welsh, and afon means river).

Other settlements four hundred miles west arrived in the early 20th century, in an area that became known as Cwm Hyfryd (Pleasant Valley). The nearby mountainous Andes reminded the Welsh much more of home. Its settlements of Esquel and Trevelin (Mill Town) remain busy today.

Today

Patagonia’s legacy also keeps resounding back in Wales, and not just in the plaque to Lewis Jones that now glows in Pool Street, Caernarfon, near the site of his old home. Patagonia has influenced writers like Richard Llewellyn, whose sequels to How Green Was My Valley take the character of Huw Morgan to Patagonia (the books are out of print, but they're worth seeking out: Up Into The Singing Mountain and Down Where The Moon Is Small also have the most evocative titles when it comes to exploring distant lands) .

The Super Furry Animals’ Gruff Rhys also made an acclaimed film about Patagonia, Separado, in 2010. In it, the Welsh singer and musician takes a road trip to hunt out distant relatives. It's as entertaining and psychedelic a journey as his brilliant albums are. Welsh playwright Marc Rees also made a play with National Theatr Wales and the Welsh language television channel S4C in 2015, 150, about the original Mimosa settlers, named after the number of them that travelled over the seas. Staged in the Royal Opera House stores in Aberdare, near where many of the settlers came form, it was a big critical hit. The National Orchestra of Wales and harpist Catrin Finch also toured Patagonia the same year to large crowds, finding them singing along with the same hwyl as the Welsh back in Wales.

The links between Wales and Patagonia continue to flourish. The Welsh Language Project continues to do its brilliant work in the region, having promoted Welsh in schools, workshops, and social activities across the Chubut Valley since 1997. Since then, a permanent teaching co-ordinator from Wales has been based in Patagonia, complemented by a network of native Argentinian Welsh speakers. The National Centre For Learning Welsh also stretches its hand far across the Atlantic to support it, offering three scholarships every year to Patagonians to study Welsh at Cardiff University or Aberystwyth University.

The Welsh voluntary organisation for young people, Urdd Gobaith Cymru, have also run annual trips for all Urdd members and young Welsh learners to travel and volunteer in Patagonia since 2011. Go to the Urdd website for details of their latest trips, and how local Urdd officers can help participants raise funds. Companies like Teithiau Tango also offer Welsh language holidays in the region, or you could set off by yourself, wild and free, just like our ancestors did so many years ago.

Because while the story of Y Wladfa may not be as simple, or romantic, as we expected, its success story still sings on, loud and true.