What do Japanese sushi and Wales have in common? The answer is Dr Kathleen Drew-Baker, a British botanist whose discoveries about seaweed in Wales helped restore Japan’s diminishing sushi industry.

Findings of marine lecturer and researcher, Dr Kathleen, off the Pembrokeshire coast, helped towards revolutionising seaweed production, supporting sushi to become the global dish that it is today.

A staple of Japanese cuisine, sushi has grown to become one of the most recognisable and popular international dishes around the world. These days, it’s easy to find a restaurant serving it wherever you go, so it’s hard to imagine a time when it might not have been. However, in the late 1940s, the end of sushi became a very real possibility.

Nori, a leafy red seaweed used in its preparation, had become scarce. Despite having been harvested along Japan’s coastlines for hundreds of years, a series of crop failures had devastated supply. Production of nori subsequently slumped into serious decline, having become too unreliable to cultivate for a country in dire need of rebuilding itself after the second world war.

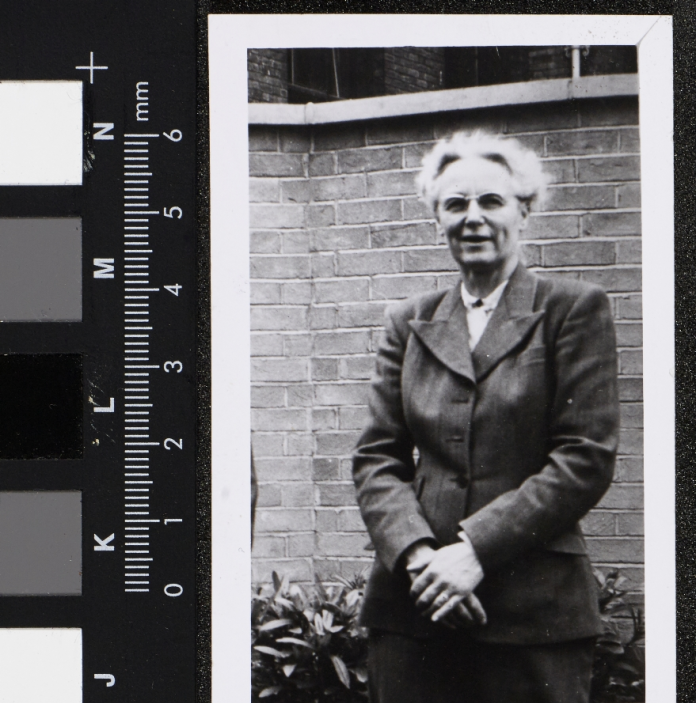

The good news was that, as well as being a crucial ingredient in the preparation of sushi, nori was also the object of study for Dr Kathleen Drew-Baker, a lecturer in botany at the University of Manchester at the time. Dr Kathleen had developed a special interest in marine and coastal botany, particularly in different types of seaweed, and these interests would go on to have an impact on Japan's sushi industry.

During a trip to the Welsh coast in 1949, Dr Kathleen discovered that the sludgy, microscopic algae found in seashells during the summer was the same species that later blossomed into seaweed in the winter – not two different breeds as was previously assumed. She realised that to kickstart a growth cycle, seaweed spores needed to hang out in old seashells to seed, meaning that nori could be produced and harvested all year round.

Unbeknownst to Dr Kathleen, her groundbreaking discoveries helped boost nori. A paper she published on the topic was later discovered by a Japanese academic who put her theory to the test. It proved to be a huge success, so much so that her findings were used as the basis to improve nori farming methods. Production of the seaweed not only bounced back, but thrived, as a result.

Now, every year in Uto, Kumamoto - a small town in southern Japan - a festival is held in honour of Dr Kathleen, who is also fondly known as ‘the Mother of the Sea’ thanks to the role she played in saving the marine algae.

Fast forward 70 years, and just a few miles from where Dr Kathleen’s discoveries supported sushi, chef Gareth Ward’s incorporation of Japanese ingredients alongside Welsh produce at one of Wales’ most renowned restaurants, Ynyshir, has led to the award of two Michelin stars.

Little did Dr Kathleen know that the results of her work would end up being enjoyed by people all over the world many years later, as well as lead to her becoming a celebrated figure 6,000 miles away in Japan!